The Spanish state is defined by a feature, often not known outside of its boundaries, which provides a better understanding of the political discourse and tensions inside of it. This feature is the fact that Spain is a state composed of several nations—territories inhabited by individuals who share a unique culture, language, economy, and above all, a feeling of belonging to a separate nation. Because of this, these people identify more with their historical nation than with the artificial mental construct of Spain.

Catalonia and the Basque Country are the two best examples of nations inside Spain. Around the world, there are countries made up of nations. Usually, these countries recognize this reality in a democratic spirit. An example of this is the United Kingdom. Although the government in London does not wish for Scotland to secede, or for Ireland to reunite, it understands that the people in each of these territories have the final say about such matters. There are other countries, like France, hostile towards cultural minorities, who have achieved such a level of cultural assimilation that territorial conflicts have practically disappeared—with the exception of Corsica. In Spain, we find that nations without state (Catalonia, Basque Country) still exist, but they have been unable to become independent. Conversely, although the Kingdom of Spain remains intact, it has been incapable of assimilating these nations. This is the strife-rich scenario we're in.

A few days ago, the King's Cup final took place, with two teams playing it, one Catalan, the other, Basque: Futbol Club Barcelona and Athletic Bilbao. The game was scheduled to be played in Madrid, at the Vicente Calderon stadium, Atletic de Madrid's home field. From a strictly soccer-only point of view, Barça won the game comfortably (0-3). Their victory gave Barça its 14th title (out of a possible 19) with Guardiola as coach. Outside of what is strictly-speaking soccer, Barça and Bilbao's followers booed the Spanish anthem at the beginning of the game—which infuriated several political and media pundits.

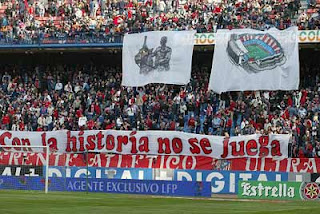

Before the match, Madrid's Autonomous Community president Esperanza Aguirre (PP) had asked that it be cancelled if anyone booed at the Spanish anthem. Once the game was over, Madrid's vice-president decried that Catalan and Basque politicians had not condemned the protest. All these unprecedented, strong-worded reactions could almost make you believe that neither political demonstrations and signs, nor politically-charged flags ever show up at the Calderon stadium. They could lead you to think that Barcelona and Bilbao fans are intolerant, while Atletic Madrid fans are the epitome of civilized behavior. You just need to google this up, and soon you realize it's not quite like that. Here are some images taken at Calderon stadium during the last few years:

Spanish flags used during Franco's dictatorship seen at Zona del Frente Atletico:

Tribute to the Austrian extremist right-wing political leader Jörg Haider:

People protesting against the removal of dicator Franco's statue from a street in Madrid:

Some guy taking advantage of the double meaning of "Cara al Sol," Falange's anthem—Falange is a still-existing fascist party founded in 1933:

People singing in suport of acts of violence against Basques, and making fun of Aitor Zabaleta, a real Sociedad fan who was killed in 1998 near Vicente Calderon stadium:

A couple of disclaimers:

1) Atletic Madrid followers come in many colors. The behavior seen in these pictures and video belongs to a minority. However, it is also true that these small groups benefit from Atletic Madrid's followers complictity in allowing such actions—and that of Madrid's and Spain's politicians.

2) Esperanza Aguirre's request to cancel the game, coming from a right-wing representative, stands in stark contrast with her absolute silence regarding violence-inciting actions and the ubiquitous presence of the flag used before the Spanish democracy, which can only be understood as a sign of support of Franco's dictatorship, which ended in 1975. Curiously, Aguirre thinks that incident-fee, peaceful actions such as the booing of the Spanish anthem are punishable, while she's never had any problem with violence-inciting rabble who are a fixture at the stadium, and who display symbols used by totalitarian regimes that ravaged Europe during the last century.

Pau Roig, blogger

@_Pau5

Pau Roig, blogger

@_Pau5

Cap comentari:

Publica un comentari a l'entrada